The art of a great exit

In my coaching work recently I’ve had some conversations with clients about making a move – ending roles and beginning new ones.

Working with them on the challenges these moves present, I’ve been reminded of the very different experiences I’ve had over the course of my career when leaving organisations. Having experienced everything from blithely wafting out the door without a care in the world or a thought for the future early on in my career to departures thrust upon me – such as the failure of our business – I have been profoundly surprised in my later career by the degree of satisfaction I have drawn from departures that I feel I have managed well.

We’ve all seen public figures – politicians and entertainers – who don’t seem to know when it’s time to leave. Occasionally a tenure is cut short and potential fails to be realised, but more often it’s a case of someone staying far too long.

With Chairs and directors, senior executives and business founders the same questions of timing arise, but I would argue that in professional life the manner of the exit matters more than the timing.

There are so many reasons why an executive or non-executive appointment comes to an end. Some, such as a business crisis, strategic redirection, acquisition or divestiture are naturally more prone to abrupt, highly emotional, angst-ridden or even explosive departures. Anyone can see that these cases call for careful management.

But even when a role ends for the most benign of reasons – such as the agreed time of the appointment having elapsed, or the agreed objectives having been achieved – it’s worth approaching every exit strategically. And I think this means contemplating your exit, and planning for it, from the moment you arrive, and engaging with the organisation, throughout your time together, in a balanced way.

The ideal exit is one where dignity, respect and fairness are available to all parties. It’s great when the relationships and networks that we’ve developed in a role continue to be available and effective for us into the future. At the very least, we want to be confident of the answer to the question “What will they say about me when I’m gone?”

Volumes have been written recently about emotional intelligence and how we use it to relate to the people that we work and interact with. Reflecting on various stages of my career, and the numerous exits along the way, I’ve also thought about the relationships I developed with the organisations I have worked with and how I managed those relationships from an emotional intelligence point of view.

I’m a person of great enthusiasm and energy. I get involved. I care about outcomes. I love my work. Never comfortable with the label of workaholic, I prefer to say that I have always found work to be the source of abundant positive emotions – gratitude, interest, pride, hope, inspiration and certainly amusement – at least six of Barbara Fredrickson’s ten – I was a poster girl for passion long before it was a watchword.

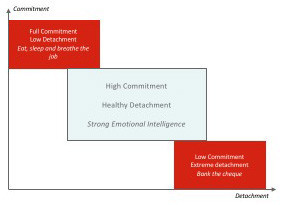

But how much passion and commitment is enough, and how much is too much?

Overinvestment in a role or an organisation is easy to identify when an exit looms – how many of us fail to update résumés, develop beyond-role capabilities and maintain our wider networks until we see the chasm of a separation opening before us?

Overinvestment in a role or an organisation is easy to identify when an exit looms – how many of us fail to update résumés, develop beyond-role capabilities and maintain our wider networks until we see the chasm of a separation opening before us?

Passion is a wonderful thing – personally and professionally – and today is at the core of what organisations increasingly demand of their talent. But I think commitment works best where it is balanced by detachment. Maintaining a healthy level of detachment – we could call it professionalism – throughout an assignment helps us to engage with an organisation in a strategic and constructive way along the journey, and prepares the space for us to disengage well when an association ends.

It’s in the nature of successful people to be inclined to high commitment, and it is certainly the practice of many organisations to recruit and reward in a way that tries to increase that commitment – incentive programs everywhere are focused on building ‘skin in the game’, often ignoring the more powerful intrinsic motivations that drive us all, and the inherent communality of interest that comes from performance satisfaction, strong brand and reputation and pride in work well done.

It also fails to recognise that excessive commitment, likely to be accompanied by limited detachment, can be every bit as dangerous to an organisation as too little. An excess of commitment, at any stage in an appointment, is likely to bring more emotions into play, and if not properly balanced by detachment, will prevent the achievement of strong EQ in carrying out the role.

Detached is not uncaring – it’s measured. Of the four emotional intelligence capabilities identified by Daniel Goldman, the first two are self awareness and self management – these both require us to step back from our emotions and see ourselves in context. We need to have perspective, and that always improves with distance. Perhaps perversely, but inevitably, achieving a healthy level of detachment was not only better for me – it was better for the organisations I worked with as well.

If we can establish the perspective to contemplate the end of an assignment or association from its very beginning, and then maintain that perspective so that we balance our commitment and detachment throughout, we can build and deliver our performance in the hope of a wonderful exit every time.